What is Functional Programming

Functional programming decomposes a problem into a set of functions. Ideally, functions only take inputs and produce outputs, and don’t have any internal state that affects the output produced for a given input.

- Well-known functional languages include the ML family (Standard ML, OCaml, and other variants) and Haskell.

- Like List and C++, Python is multi-paradigm language that support several different approaches. You can write programs or libraries that are largely procedural, object-oriented, or functional.

- In a large program, different sections might be written using different approaches; the GUI might be object-oriented while the processing logic is procedural or functional, for example.

- Functional style discourages functions with side effects that modify internal state or make other changes that aren’t visible in the function’s return value.

- Python won’t go to the extreme of avoiding all I/O or all assignments; instead, they’ll provide a functional-appearing interface but will use non-functional features internally. For example, the implementation of a function will still use assignments to local variables, but won’t modify global variables or have other side effects.

- Functional programming can be considered the opposite of object-oriented programming. But in Python you might combine the two approaches by writing functions that take and return instances representing objects in your application.

Some core features:

- Input data flows through a set of functions. Each function operates on its input and produces some output.

- Functional programming tries to avoid mutable data types and state changes as much as possible.

- It works with the data that flow between functions.

- The use of recursion rather than loops or other structures as a primary flow control structure

- A focus on lists or arrays processing

- A focus on what is to be computed rather than on how to compute it

- The use of pure functions that avoid side effects

- The use of higher-order functions

Why should you avoid objects and side effects in Functional programming?

There are theoretical and practical advantages to the functional style: Formal provability. Modularity. Composability. Ease of debugging and testing.

Iterator, Iterable

- Why iteration need two concepts: iterator and iterable? Because It can decouples the iteration algorithms from container data structures.

- Maybe we can say there are 3 concepts: iterator, not pure iterable, and pure iterable. iter(pure_iterable) return fresh iterator, iter(not_purt_iterable) return itself.

- List object is classic iterable, but not iterator.

- iterator is an important foundation for writing functional-style programs.

Iterable concept (official document)

- Any object that supports iter() and return iterator is said to be “iterable.”

- list, str, and tuple are classical example of iterables

- Some non-sequence types like dict, file objects are iterables.

- Objects of any classes you define with an

__iter__()method or with a__getitem__()method that implements sequence semantics are iterables. - Iterables can be used in a for loop and in many other places where a sequence is needed (zip(), map(), …).

Iter()

- When an iterable object is passed as an argument to the built-in function iter(), it returns an iterator for the object. This iterator is good for one pass over the set of values.

- When using iterables, it is usually not necessary to call iter() or deal with iterator objects yourself. The for statement does that automatically for you, creating a temporary unnamed variable to hold the iterator for the duration of the loop.

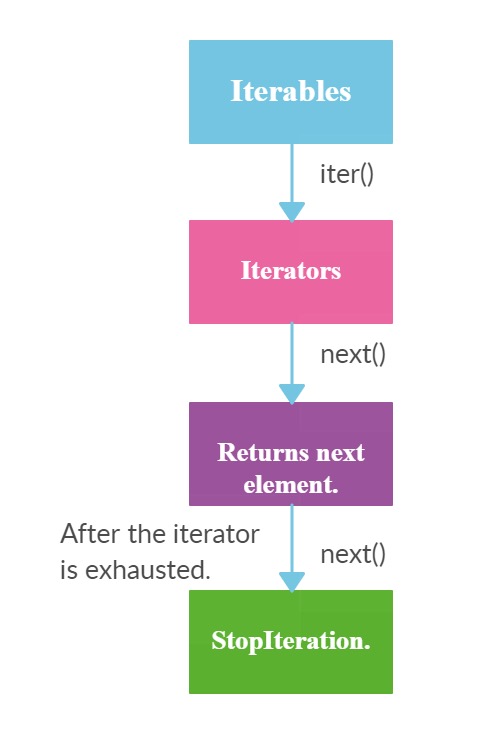

Iterator concept

- An iterator object representing a stream of data. Repeated calls to the iterator’s

__next__()method (or passing it to the built-in function next()) return successive items in the stream. - Iterator just go forward, never backward.

- When no more data are available a StopIteration exception is raised instead.

- The iterator objects themselves are required to support the following two methods, which together form the iterator protocol:

-

iterator.__iter__(), iterator.__next__()

-

- Iterators are required to have an

__iter__()method that returns the iterator object itself so every iterator is also iterable and may be used in most places where other iterables are accepted. (One notable exception is code which attempts multiple iteration passes. ) - CPython does not consistently apply the requirement that an iterator define

__iter__(). - Every iterator is also an iterable, but not every iterable is an iterator. For example, list and string are iterable but they are not iterator.

- A container object (such as a list) produces a fresh new iterator each time you pass it to the iter() function or use it in a for loop. But Attempting this with an iterator will just return the same exhausted iterator object used in the previous iteration pass, making it appear like an empty container.

- An iterator can be created from an iterable by using the function

iter().s = "GFG"thens = iter(s)thennext(s) - Iterators are used to allow user-defined classes to support iteration.

-

__iter__()function returns an iterator for the given object (like list, set, tuple, etc. or custom objects). It creates an object that can be accessed one element at a time using__next__()function.

Iterator vs. Iterable

lst = [1,2,3]

i_lst = iter(lst)

- lst is iterable, but not iterator.

- i_lst is iterator and also iterable. i_lst is list_iterator object

An ITERABLE is:

- an object that defines iter that returns a fresh ITERATOR, or it may have a getitem method suitable for indexed lookup.

An ITERATOR is an object:

- with a

__next__method that:- returns the next value in the iteration

- updates the state to point at the next value

- signals when it is done by raising StopIteration

- with state that remembers where it is during iteration,

- and that is self-iterable (CPython does not consistently apply ).

Difference at iter()

__iter__() is semantically different for iterables and iterators.

- In iterators, the method returns the iterator itself, which must implement a

.__next__()method. - In iterables, the method should yield items on demand. It return fresh iterator.

Other differences

- Pure iterables typically hold the data themselves.

- In contrast, iterators don’t hold the data but produce it one item at a time, depending on the caller’s demand.

- Therefore, iterators are more efficient than iterables in terms of memory consumption.

iteration example:

class countdown(object):

def __init__(self,start):

self.start = start

def __iter__(self):

return countdown_iter(self.start)

class countdown_iter(object):

def __init__(self, count):

self.count = count

def __next__(self):

if self.count <= 0:

raise StopIteration

r = self.count

self.count -= 1

return r

Then:

>>> c = countdown(5)

>>> for i in c:

... print(i, end=' ')

...

5 4 3 2 1

>>>

- c is iterable. 5 is it’s data.

iter(c)will return fresh iterator (without__iter__). -

iter(c)is technically not iterator because it have no__iter__. - You can make

iter(c)a iterator when you add def__iter__(self): return self to countdown_iter class.

Iteration FAQ

If a object support next(), but not support iter(). is it a iterator?

It is NOT iterator. But CPython doesn’t consistently apply.

If object A support iter() and iter(objectA) return an object which just support next() but not iter(). Then object A is still iterable?

If no iter() then NOT iterator, so not iterable. But CPython doesn’t consistently apply.

Why so many blogs conclude the differences between iterator and iterable, when iterator is a iterable as well?

the differnence is one thing: iterator iter() itself, but iterable iter() another object.

Iterator should not be called as iterable even it supoort iter(), Because iter() return itself instead of a fresh iterator? Or just should not be called as pure iterable?

Yes, you can add the pure iterable concept.

for loop in Python

The for...in is always used in combination with an iterable object.

The Python for statement iterates over the members of a sequence in order, executing the block each time. It don’t like JavaScript, or C

for x in obj:

# statements

Underneath the covers

_iter = iter(obj) # Get iterator object

while 1:

try:

x = _iter.__next__() # Get next item

except StopIteration: # No more items

break

# statements

...

Understand how for...in loop iterate over a iterable object:

- What the core point is that it is a lazy processing.

- I am going to make two example to display how

for...inloop work underneath the cover. First one is loop over a enumerate object, and second one is loop over a range object, it raise error.

First example:

lst = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

for i, value in enumerate(lst):

lst.pop(i)

print(lst)

There are No error raising for these codes, but they are not work as expected. the code print: [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]

enumerate object is generator object which will yield value from lst. It is lazy process. When lst change, value from enumerate object change as well, but i is keep going.

for...in is equivalent to:

_iter = iter(enumerate_obj)

while 1:

try:

x = _iter.__next__()

except StopIteration:

break

# statements

enumerate() is equivalent to:

def enumerate(lst):

n = 0

for i in lst:

yield n, i

n += 1

Second example:

lst = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

for i in range(len(lst)):

lst.pop(i)

This code will raise IndexError. range() is iterable, but len(lst) in range() parameter here have been replace with constant value 10. Because len(lst) is not a lazy process. it don’t change any more. So i will up to 9.

So the codes are equivalent to:

for i in range(9):

lst.pop(i)

Generator

What is Generator

- Generators are a special class of functions that simplify the task of writing iterators.

- Generator functions is a convenient shortcut to building iterators.

- Regular functions compute a value and return it, but generators return an iterator that returns a stream of values.

- When you call a generator function, it doesn’t return a single value; instead it returns a generator object that supports the iterator protocol.

- If a container object’s

__iter__()method is implemented as a generator, it will automatically return a generator object supplying the__iter__()and__next__()methods. - There are two ways to create Generator: generator expression and generator function

- If you create a list to sum the first n. When n is really big, then it consume lots of memory. Not acceptable. Generator (iterator) will perform the job much better.

- Note: a generator will provide performance benefits only if we do not intend to use that set of generated values more than once.

- When you use recursion for generator, you need to clear the subgenerator concept. Otherwise, it won’t work as you expect.

Generator is not pure iterable

Generator is iterator, but it is not pure iterable. That means iter(generator) return itself instead of a fresh iterator.

Basic Example

clone python’s built-in range() function:

def my_range(start, stop, step = 1):

if stop <= start:

raise RuntimeError("start must be smaller than stop")

i = start

while i < stop:

yield i

i += step

for k in my_range(10, 50, 3):

print(k)

Create Generator

Generator functions

Generator function is defined similar to normal function but there is only one difference, it is using yield keyword to return value used for each iteration.

Any function containing a yield keyword is a generator function; this is detected by Python’s bytecode compiler which compiles the function specially as a result.

Generator function return a lazy iterator. This iterator also call generator object.

Generator expression(also call generator comprehension)

- Generator expressions provide an additional shortcut to build generators out of expressions similar to that of list comprehensions.

- If the generated expressions are more complex, involve multiple steps, or depend on additional temporary state, Using generator function .

generator comprehension:

>>> nums_squared_gc = (num**2 for num in range(5))

List comprehension:

>>> nums_squared_lc = [num**2 for num in range(5)]

>>> nums_squared_lc

[0, 1, 4, 9, 16]

>>> nums_squared_gc

<generator object <genexpr> at 0x107fbbc78>

The difference

We can think of list comprehensions as generator expressions wrapped in a list constructor:

# list comprehension

doubles = [2 * n for n in range(50)]

# same as the list comprehension above

doubles = list(2 * n for n in range(50))

The difference between generator and list comprehensions is that generator comprehension create lazy generator. it won’t consume all memory it need at one time. But list comprehension will, because list constructor run through the generator.

Subgenerator (yield from)

- You can use yield from to read data from an other generator.

- There is Subgenerator concept, read more at PEP380.

- When you use recursion in generator you will meet some weird issue. That is because you have no subgenerator concept. You need to use yield from for each subgenerator. Otherwise you need to use for to run over it (sometime works, sometime not works). Because Generator return Generator Object! it is different from normal function.

Understand subgenerator

- A Python generator is a form of coroutine, but has the limitation that it can only yield to its immediate caller. This means that a piece of code containing a yield cannot be factored out and put into a separate function in the same way as other code.

- Performing such a factoring causes the called function to itself become a generator, and it is necessary to explicitly iterate over this second generator and re-yield any values that it produces.

- If yielding of values is the only concern, this can be performed without much difficulty using a loop.

- However, if the subgenerator is to interact properly with the caller in the case of calls to send(), throw() and close(), things become considerably more difficult. As will be seen later, the necessary code is very complicated, and it is tricky to handle all the corner cases correctly.

Understand yield from

- yield from is a new syntax. You can check the codes for yield from in PEP380.

- This new syntax empowers you to refactor generators in a clean way by making it easy to yield every value from an iterator (which a generator conveniently happens to be).

- yield from also lets you chain generators together so that values bubble up and down the call stack without code having to do anything special.

- Let’s get one thing out of the way first. The explanation that yield from g is equivalent to for v in g: yield v does not even begin to do justice to what yield from is all about.

- Because, if all yield from does is expand the for loop, then it does not warrant adding yield from to the language and preclude a whole bunch of new features from being implemented in Python 2.x. PEP380 have the detail.

What yield from does is it establishes a transparent bidirectional connection between the caller and the sub-generator:

- The connection is “transparent” in the sense that it will propagate everything correctly too, not just the elements being generated (e.g. exceptions are propagated).

- The connection is “bidirectional” in the sense that data can be both sent from and to a generator.

Example of using recursion in generator:

You can’t print 0,1,2,3,4 from following code:

def generator_recursion(n):

if n < 0:

return

else:

generator_recursion(n-1)

yield n

gr = generator_recursion(4)

for k in gr:

print(k)

You need to use yield from:

def generator_recursion(n):

if n < 0:

return

else:

yield from generator_recursion(n-1)

yield n

Passing values into a generator

In Python 2.5 there’s a simple way to pass values into a generator. yield became an expression, returning a value that can be assigned to a variable or otherwise operated on:

val = (yield i)

val = (yield i) + 10

(Recommend that you always put parentheses around a yield expression.)

Values are sent into a generator by calling its .send(value) method. This method resumes the generator’s code and the yield expression returns the specified value.

Simple example:

def counter(maximum):

i = 0

while i < maximum:

val = (yield i)

# If value provided, change counter

if val is not None:

i = val

else:

i += 1

The value of val is always None when regular __next__() method is called. When .send(value) is called. the val will be the value

How do send(value) resumes the generator?

- When calling next(), the code resume from the next line which after last yield.

- When calling

.send(value), the code resume from the last yield! And also yield a value back to.send(value)function (likenext()do). - You can even can’t send(value) at the very beginning, otherwise get error: TypeError: can’t send non-None value to a just-started generator

Built-in functions for iterators

map() and filter() duplicate the features of generator expressions:

map(f, iterA, iterB, …) returns an iterator over the sequence f(iterA[0], iterB[0]), f(iterA[1], iterB[1]), f(iterA[2], iterB[2]), ….

filter(predicate, iter)

returns an iterator over all the sequence elements that meet a certain condition, and is similarly duplicated by list comprehensions.

enumerate(iter, start=0)

counts off the elements in the iterable returning 2-tuples containing the count (from start) and each element.

for item in enumerate(['subject', 'verb', 'object']):

print(item)

(0, 'subject')

(1, 'verb')

(2, 'object')

Sorted(iterable, key=None, reverse=False)

collects all the elements of the iterable into a list, sorts the list, and returns the sorted result. The key and reverse arguments are passed through to the constructed list’s sort() method.

The any(iter) and all(iter)

built-ins look at the truth values of an iterable’s contents. any() returns True if any element in the iterable is a true value, and all() returns True if all of the elements are true values

zip(iterA, iterB, …)

takes one element from each iterable and returns them in a tuple

itertools module

The module standardizes a core set of fast, memory efficient tools that are useful by themselves or in combination. Together, they form an “iterator algebra” making it possible to construct specialized tools succinctly and efficiently in pure Python.

Combinatoric iterators:

permutations(iterable, r=None)

- Return successive r length permutations of elements in the iterable.

- Return a iterable object, elements are tuple.

- Elements are treated as unique based on their position, not on their value.

>>> print([p for p in permutations('pro')])

[('p', 'r', 'o'), ('p', 'o', 'r'), ('r', 'p', 'o'), ('r', 'o', 'p'), ('o', 'p', 'r'), ('o', 'r', 'p')]

product(*iterables, repeat=1)

Cartesian product of input iterables. What Cartesian product do is as following: product('ABCD', 'xy') --> Ax Ay Bx By Cx Cy Dx Dy

repeat parameter

product(A, repeat=4) means the same as product(A, A, A, A).

# product(range(2), repeat=3) --> 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

This function is roughly equivalent to the following code, except that the actual implementation does not build up intermediate results in memory:

def product(*args, repeat=1):

pools = [tuple(pool) for pool in args] * repeat

result = [[]]

for pool in pools:

result = [x+[y] for x in result for y in pool]

for prod in result:

yield tuple(prod)

functools module

A higher-order function takes one or more functions as input and returns a new function. The most useful tool in this module is the functools.partial() function.

functools.partial()

The constructor for partial() takes the arguments (function, arg1, arg2, …, kwarg1=value1, kwarg2=value2). The resulting object is callable, so you can just call it to invoke function with the filled-in arguments.

Example:

import functools

def log(message, subsystem):

"""Write the contents of 'message' to the specified subsystem."""

print('%s: %s' % (subsystem, message))

...

server_log = functools.partial(log, subsystem='server')

server_log('Unable to open socket')

functools.reduce()

functools.reduce() takes the first two elements A and B returned by the iterator and calculates func(A, B)

Syntax: functools.reduce(func, iterable[, initializer]) func must be a function that takes two elements and returns a single value.

reduce() is roughly equivalent to the following Python function:

def reduce(function, iterable, initializer=None):

it = iter(iterable)

if initializer is None:

value = next(it)

else:

value = initializer

for element in it:

value = function(value, element)

return value

Example: from functools import reduce

def factorial(n):

return reduce(lambda x, y: x * y, range(1, n + 1) or [1])

factorial(4)

Small functions and the lambda expression

When writing functional-style programs, you’ll often need little functions that act as predicates or that combine elements in some way.

If there’s a Python built-in or a module function that’s suitable

operator — Standard operators as functions

The operator module exports a set of efficient functions corresponding to the intrinsic operators of Python. For example, operator.add(x, y) is equivalent to the expression x+y.

from operator import itemgetter

student_tuples = [

('john', 'A', 15),

('jane', 'B', 12),

('dave', 'B', 10),

]

sorted(student_tuples, key=itemgetter(2))

# equal to:

sorted(student_tuples, key=lambda student: student[2])

# [('dave', 'B', 10), ('jane', 'B', 12), ('john', 'A', 15)]

one way to write small functions is to use the lambda expression. (not recommend)

An alternative is to just use the def statement and define a function in the usual way. (recommend)

Recursion

Recursion introduce

In most case, recursion won’t be a good choice.

- Recursive implementations often consume more memory than non-recursive ones.

- In some cases, using recursion may result in slower execution time.

Traversal of tree

- Recursion is good for Traversal of tree-like data structures.

Recursion in Python

- You can find out what Python’s recursion limit is with a function from the sys module called getrecursionlimit().

- You can change it, too, with setrecursionlimit()

- When you call a function in Python, the interpreter creates a new local namespace so that names defined within that function don’t collide with identical names defined elsewhere.

functional features functions

Build-in functions: map() filter() reduce().

map(function, iterable, *iterables)

- Return an iterator that applies function to every item of iterable, yielding the results.

- If additional iterables arguments are passed, function must take that many arguments and is applied to the items from all iterables in parallel.

- With multiple iterables, the iterator stops when the shortest iterable is exhausted.

- For cases where the function inputs are already arranged into argument tuples, see itertools.starmap().

- map() is Functional Style in Python. Although it can be replace by for loop.

Advantage

- Since map() is written in C and is highly optimized, its internal implied loop can be more efficient than a regular Python for loop.

- map() returns a map object, which is an iterator that yields items on demand. Using map() is good for memory consumption. This is compare to Python for loop.

filter(function, iterable)

Construct an iterator from those elements of iterable for which function is true.

- Note that filter(function, iterable) is equivalent to the generator expression (item for item in iterable if function(item)) if function is not None and (item for item in iterable if item) if function is None.

FAQ

- What is the difference between generator and coroutine

- What is the difference between generator object and generator function?